What is a thread?

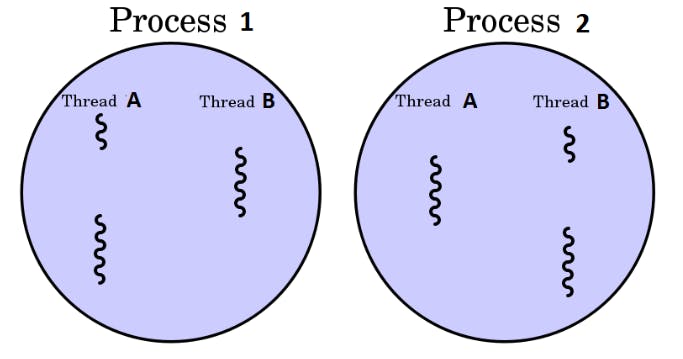

Operating System (OS) threads, often just called threads, are a way for a program to split itself into two or more simultaneously (or seemingly simultaneously) running tasks.

Here's a simple analogy: imagine you're cooking a meal. The entire process of cooking the meal is like a program. Now, you could do each task one at a time: chop the vegetables, then cook the vegetables, then clean the dishes, and so on. This is like a single-threaded program.

But if you're a skilled cook, you might do several things at once: while the vegetables are cooking, you start cleaning the dishes. Each of these tasks that you're doing at the same time is like a thread.

In a computer, each thread represents a separate flow of control within a given process. Threads are useful because they allow a program to do multiple things at once (like downloading a file while still responding to user input), and they can make programs more efficient by taking advantage of multiple processors or cores on a computer.

Maximum number of threads an operating system can support

The maximum number of threads that an operating system can support is primarily determined by the resources available on the system, such as memory and CPU capacity. Each thread requires some overhead in terms of memory for its stack, and CPU time to execute its instructions. Therefore, the more memory and CPU capacity you have, the more threads you can theoretically support.

However, the number of threads that can actually be executing instructions at any given moment is determined by the number of CPU cores. Each core can execute one thread at a time (or two threads in the case of hyper-threading, a technology used by some CPUs). So, if you have a quad-core processor, it can execute four threads simultaneously.

If a system has more threads than cores, the operating system uses a technique called context switching to allow all the threads to make progress. Context switching involves saving the state of a currently executing thread, and then loading the state of another thread to start or resume its execution. This happens very quickly, so it gives the illusion that all the threads are running at the same time, even though only a subset of them are actually executing at any given moment.

However, context switching is not free. It takes time and resources, so if you have too many threads, your system can spend more time switching between threads than actually doing useful work. This is known as thrashing.

In practice, the optimal number of threads for a particular program or system depends on many factors, including the nature of the work being done, the characteristics of the hardware, and the design of the operating system's scheduler. As a rule of thumb, for CPU-bound tasks (tasks that spend most of their time executing instructions, rather than waiting for I/O), having a number of threads roughly equal to the number of cores can be a good starting point.

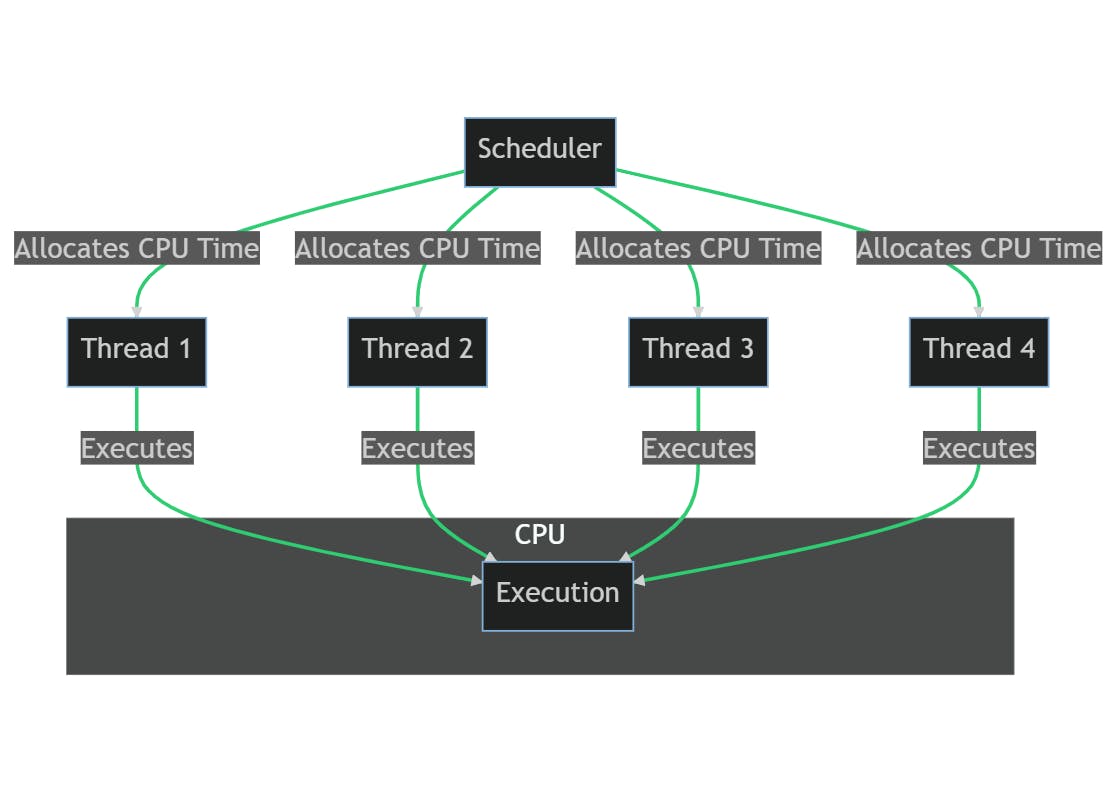

The thread scheduler

A thread scheduler, also known as a process scheduler, is a part of the operating system that decides which thread should be executed by the processor at any given time. You can think of it like a thread orchestrator. The scheduler is responsible for managing all the threads within the system and ensuring that each thread gets a fair share of the processor's time, based on its priority and the scheduling policy.

The scheduler works by using a technique called context switching. When it's time to switch from one thread to another, the scheduler saves the current state of the running thread (this is known as a context save), and then loads the saved state of the next thread to be run (this is a context restore). This allows the next thread to pick up where it left off the last time it was running.

There are several different scheduling algorithms that a scheduler can use, and the choice of algorithm can have a big impact on the performance and responsiveness of the system. Some common scheduling algorithms include:

First-Come, First-Served (FCFS): This is the simplest scheduling algorithm. The first thread that requests the CPU gets it. The main disadvantage of this method is that short tasks may have to wait for very long tasks to complete.

Shortest Job Next (SJN): This algorithm selects the thread with the smallest total execution time. This minimizes waiting time for all processes, but it requires knowing in advance how long each thread will run, which is not usually possible.

Round Robin (RR): This algorithm allocates a fixed time slot to each thread. When a thread's time slot expires, it is moved to the back of the queue and the next thread in the queue is given the CPU. This is a simple and fair algorithm, but it may not be the most efficient if threads have very different lengths or priorities.

Priority Scheduling: This algorithm assigns a priority to each thread, and the thread with the highest priority is given the CPU. If two threads have the same priority, FCFS or RR can be used to decide between them.

Different operating systems may use different scheduling algorithms, or they may allow the user to choose between several options. For example, Linux uses a scheduler called the Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS), which tries to ensure that each thread gets a fair share of the CPU, while also taking into account priority levels. Windows uses a priority-based, preemptive scheduling algorithm, where higher priority threads are given preference over lower priority ones.

In addition to the scheduling algorithm, the behavior of the scheduler can also be influenced by other factors, such as the current load on the system, the number of available CPUs, and the specific behavior of the threads themselves (for example, whether they are I/O-bound or CPU-bound).

Thread lifecycle

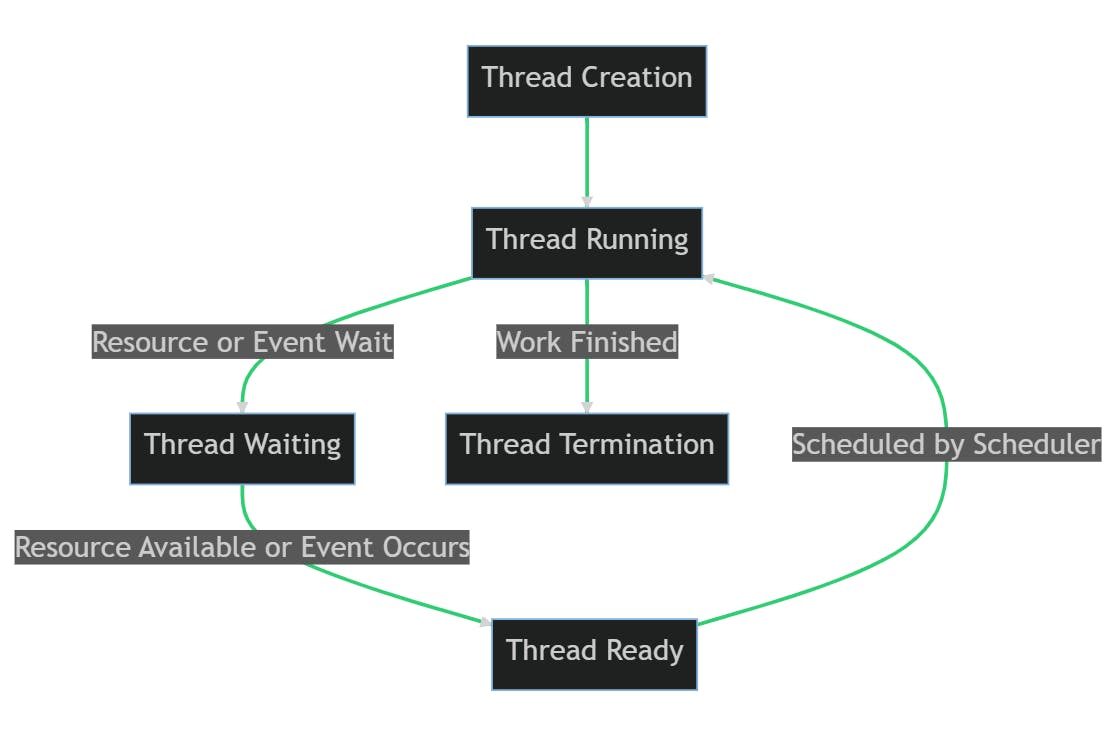

The lifecycle of an operating system thread typically involves the following stages:

Thread Creation: A thread is created by a process. The process can be a single-threaded process creating its first thread, or a multi-threaded process creating an additional thread. The new thread starts running a specific function or method.

Thread Running: Once created, the thread is in the running state. The thread scheduler decides when the thread gets to run. When it's the thread's turn, it starts executing its instructions.

Thread Waiting: Sometimes, a thread needs to wait for a resource to become available (like waiting for input/output operations to complete), or for an event to occur. In this case, the thread is put into a waiting or blocked state. While the thread is waiting, the CPU can switch to execute another thread.

Thread Ready: When the resource becomes available or the event occurs, the thread moves to the ready state. It's now ready to run again and is waiting for the thread scheduler to give it a turn on the CPU.

Thread Termination: When the thread has finished its work, it terminates. This can happen either because the thread's function has returned, or because the thread has been explicitly killed. Once a thread is terminated, its resources are returned to the system.

These stages can repeat multiple times during the life of a thread. For example, a thread might go from running to waiting to ready to running again, multiple times before it finally terminates.

In the above diagram:

The thread is created and starts running.

If the thread needs to wait for a resource or an event, it enters the waiting state.

Once the resource is available or the event occurs, the thread becomes ready to run again.

When the thread scheduler gives it a turn, the thread starts running again.

Finally, when the thread has finished its work, it terminates.

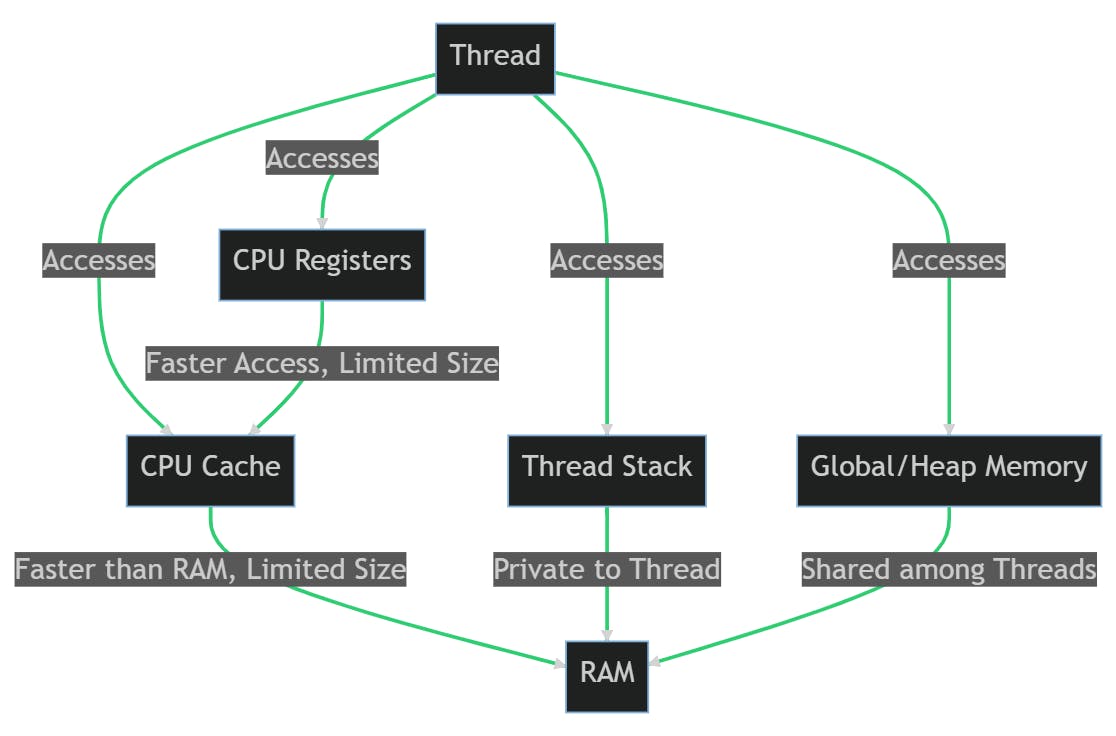

Thread memory access

When a thread is created, it gets its own private stack in the main memory (or RAM). The stack is a region of memory where the thread stores local variables and function call information. Each thread's stack is separate from the stacks of other threads, which helps to prevent threads from interfering with each other's data. However, threads within the same process can access the process's global and heap memory, which is shared among all threads in the process.

The thread stack is structured as a series of stack frames, one for each function call that the thread is currently in the middle of. Each stack frame contains the local variables for that function call, as well as some bookkeeping information that's used to resume the function when it's time to return. The stack grows and shrinks as functions are called and returned.

In addition to RAM, threads also make use of CPU registers and cache. CPU registers are small amounts of storage that are built directly into the CPU. They're used to hold the data that the thread is currently working with. The cache is a small, fast type of memory that's used to hold frequently accessed data, to speed up memory access.

In the above diagram:

The thread can access CPU registers, which provide the fastest access but have a limited size.

The thread can also access the CPU cache, which is faster than RAM but also has a limited size.

The thread has its own private stack in RAM.

The thread can also access global and heap memory, which is shared among all threads in the process.

Multithreading memory access implications

Data is loaded into CPU cache and registers as part of the process of executing a thread's instructions. The CPU uses a hierarchy of storage areas - registers, cache, and main memory (RAM) - to hold the data it needs to execute instructions.

Registers are the smallest and fastest type of storage. They are located inside the CPU and are used to hold the data that the CPU is currently working with. Each CPU instruction specifies the registers that it uses for its operands.

The CPU cache is a larger, but still relatively fast, type of storage. It's used to hold frequently accessed data, in order to speed up memory access. The CPU automatically loads data into the cache from main memory when it predicts that the data will be used soon. This prediction is based on the principle of locality, which states that data that has been used recently, or that is near data that has been used recently, is likely to be used again soon.

However, managing the cache and registers can lead to several types of issues:

Cache Coherency: In a multi-core system, each core has its own cache. If two cores have cached the same memory location and one of them changes the cached data, the other core's cache becomes out of date or "stale". This is known as a cache coherency problem. To solve this, CPUs use a variety of protocols to ensure that all cores have a consistent view of the data. This issue is indirectly what causes the famous race condition issues in multithreading.

Cache Misses: If the CPU needs data that is not in the cache, it has to fetch the data from the main memory, which is much slower. This is known as a cache miss. The CPU tries to minimize cache misses by predicting which data will be used and preloading it into the cache, but these predictions are not always accurate.

Register Allocation: The CPU has a limited number of registers, and deciding which data to keep in the registers (register allocation) is a complex problem. Compilers use a variety of techniques to try to keep the most frequently used data in the registers, but these techniques are not always perfect.

Context Switching: When the CPU switches from one thread to another (a context switch), it has to save the current state of the registers and then load the saved state for the new thread. This can be time-consuming, especially if the data for the new thread is not in the cache and has to be fetched from the main memory.

These issues add complexity to the design of CPUs and operating systems, but they are necessary to manage the trade-off between the speed of registers and cache and the larger size of the main memory.

Sneak to your OS threads state

Let's see an example of how can we monitor the threads state of a given process in Windows OS.

In Windows, you can monitor the usage and state of operating system threads using the built-in Task Manager and Performance Monitor tools. Here's how you can use each tool:

Task Manager:

Press

Ctrl + Shift + Escto open Task Manager.If Task Manager opens in compact mode, click

More detailsto switch to the full view.Click on the

Detailstab to see a list of all running processes. Each process can have one or more threads.Right-click on the column headers in the table, and then click

Select columns.Check the

Threadsbox to show the number of threads each process is using.

Performance Monitor:

Press

Win + Rto open the Run dialog, typeperfmon, and pressEnterto open Performance Monitor.In the left pane, expand

Monitoring Toolsand then clickPerformance Monitor.Click the

+button on the toolbar to add a new counter.In the

Add Countersdialog, expandThreadand then select the counters you're interested in, such as% Processor Time(the percentage of elapsed time that the thread used the processor) orThread State(the current state of the thread).Click

Add >>to add the selected counters, and then clickOK.The selected counters will be added to the graph in the main Performance Monitor window, where you can monitor them in real time.

Remember that interpreting the data from these tools can be complex, as the behavior of threads can be influenced by many factors, such as the system's current load, the behavior of other threads, and the scheduling policies of the operating system.

Conclusion

In conclusion, threads are a fundamental concept in operating systems and concurrent programming. They allow a program to perform multiple tasks simultaneously, improving the efficiency and responsiveness of the system. However, they also introduce complexity, as they require careful coordination to avoid problems like race conditions.

The lifecycle of a thread involves several stages, from creation to termination, and the thread scheduler plays a crucial role in managing these stages and deciding which thread gets to run at any given time.

Threads interact with the system's memory hierarchy, including CPU registers, cache, and RAM, to execute their instructions. This interaction can lead to issues like cache coherency problems and cache misses, which need to be managed by the CPU and the operating system.

Monitoring thread usage and state can be done using built-in tools in the operating systems. These tools provide valuable insights into the system's performance and can help identify potential issues.

Understanding threads and how they work is essential for anyone working with operating systems or developing multi-threaded applications. It provides the foundation for creating efficient and reliable software that can take full advantage of the system's resources.

![Java multithreading explained: It all starts from the OS [Part 1]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1684758531528/7b6e9329-600f-4e7f-827a-82d185658909.jpeg?w=1600&h=840&fit=crop&crop=entropy&auto=compress,format&format=webp)