Java Multithreading explained: The Java Virtual Machine abstraction [Part 2]

The Java Virtual Machine in a Nutshell

The Java Virtual Machine (JVM) is an abstract computing machine that enables a computer to run a Java program. There are three notions of the JVM: specification, implementation, and instance.

Specification: This is a document that formally describes what is required of a JVM implementation. Having a single specification ensures all implementations are interoperable.

Implementation: This is a program that meets the requirements of the JVM specification. An implementation is a computer program that is designed to execute code that is written in the Java programming language. JVMs are available for many hardware and software platforms.

Instance: Each JVM instance runs a computer program from start to finish. The program is written in Java or another language that is compiled to Java bytecode.

The JVM performs four main tasks:

Loads code: The JVM loads bytecode from .class and .jar files.

Verifies code: The JVM verifies the correctness of the loaded bytecode. This is a complex process that ensures the code is safe to execute.

Executes code: The JVM interprets the bytecode and executes it. This is done either by interpreting the bytecode one instruction at a time or by using a just-in-time compiler (JIT) that translates the bytecode into machine code and then executes that.

Provides runtime environment: The JVM provides a runtime environment in which Java bytecode can be executed. This includes handling tasks such as memory management and exception handling.

The process starts with the Java source code (.java file), which is then compiled by the Java compiler into bytecode (.class file). This bytecode is then interpreted by the Java Virtual Machine (JVM), which interacts with the operating system to execute the code. The JVM provides a runtime environment for the bytecode, handling tasks such as memory management and exception handling.

JVM thread abstraction

A thread in the context of Java and the JVM is a lightweight, independent unit of execution within a program. Each thread has its own call stack but shares access to the common heap memory where objects are stored. This allows for concurrent execution of parts of a program, which can lead to more efficient use of CPU resources, especially on multi-core systems.

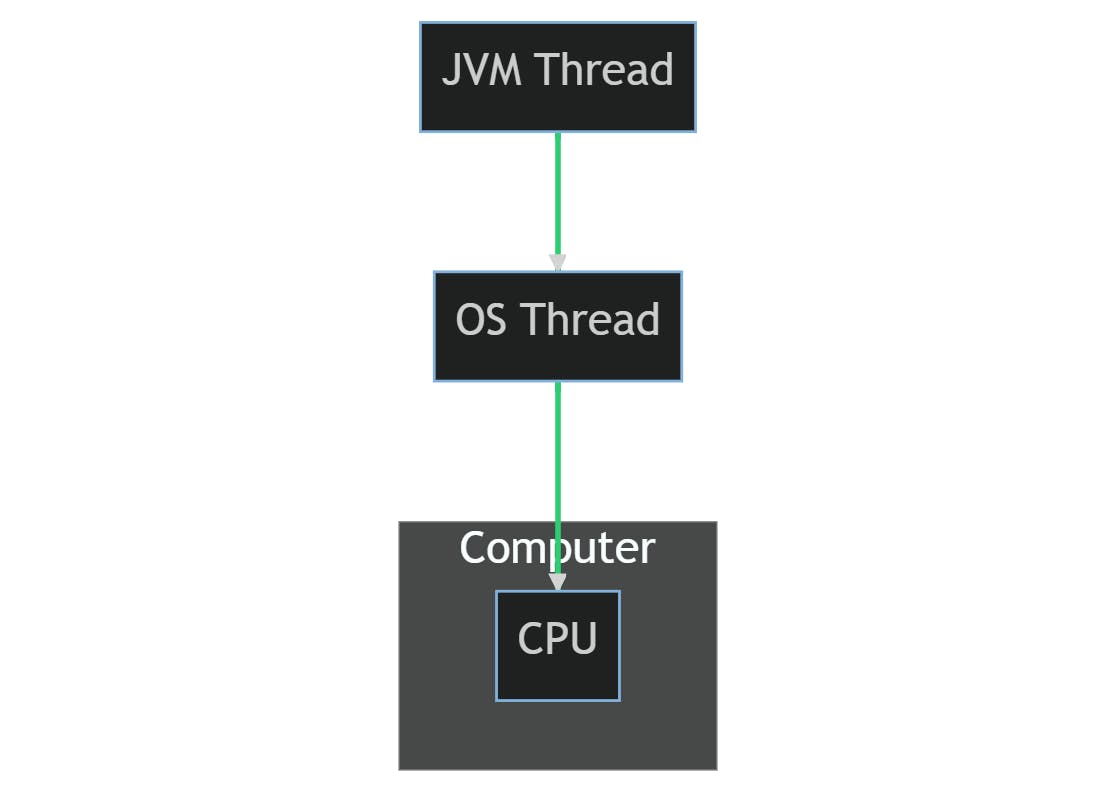

In the JVM, threads are mapped to native operating system threads. This means that when you create a new thread in Java (using the Thread class or by implementing Runnable), the JVM communicates with the operating system to create a new native thread. This native thread is then managed by the operating system's scheduler, which determines when and how long the thread gets to use CPU resources, as described in my previous article.

The JVM does not have control over the scheduling of threads - this is entirely up to the operating system. However, the JVM does provide a level of abstraction over the underlying operating system threads, allowing Java programs to be written in a platform-independent way. This means you can write multithreaded Java code without worrying about the specifics of how threads are handled on different operating systems.

In this diagram, you can see that a JVM thread is mapped to an OS thread, which is then scheduled for execution on the CPU by the operating system. This allows Java programs to be written in a platform-independent way, as the JVM provides a level of abstraction over the underlying OS threads.

The Java Memory Model

The Java Memory Model (JMM) is a part of the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) specification that describes how threads in a Java program interact through memory. It defines the behaviour of shared variables in multithreaded programs.

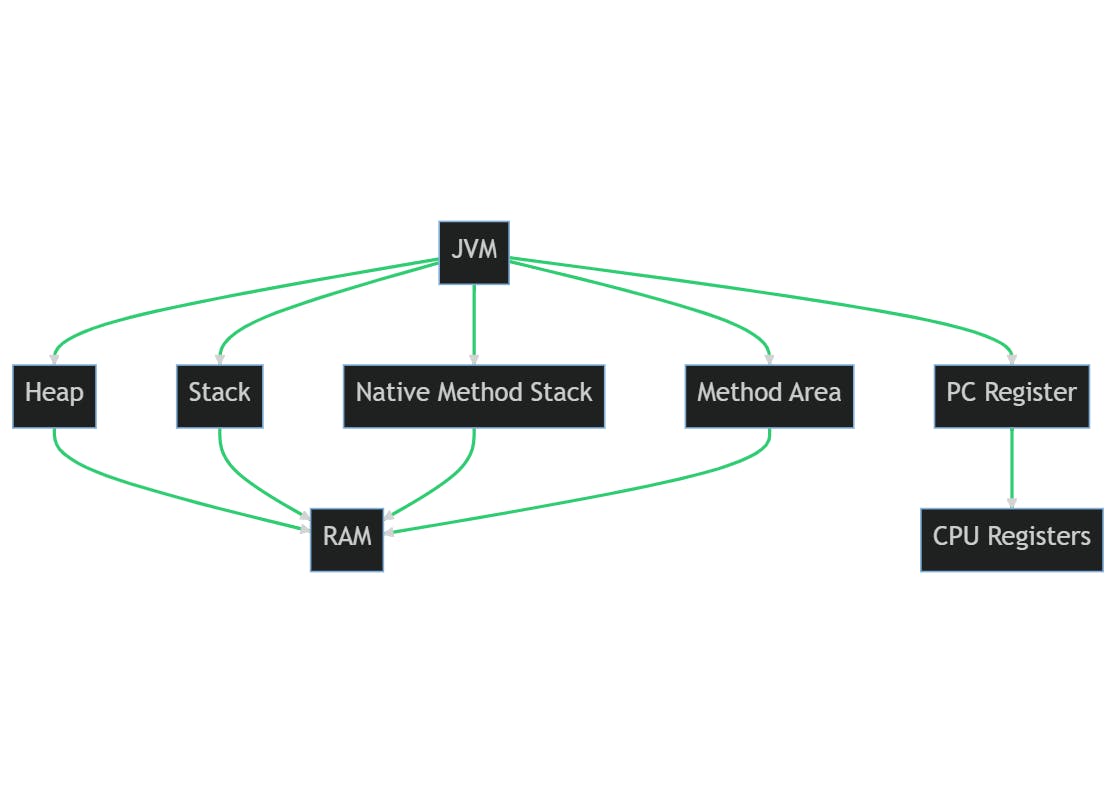

Here are the key components of the JVM memory model:

Heap: This is the runtime data area from which memory for all class instances and arrays is allocated. It is shared among all Java Virtual Machine threads.

Stack: Each JVM thread has a private JVM stack, created at the same time as the thread. A JVM stack stores frames. A frame is used to store data and partial results, as well as to perform dynamic linking, return values for methods, and dispatch exceptions.

Program Counter (PC) Register: Each JVM thread has its own PC Register. At any point, each Java Virtual Machine thread is executing the code of a single method, known as the current method for that thread. If that method is not native, the PC register contains the address of the Java Virtual Machine instruction currently being executed.

Native Method Stack: It contains all the native methods used in the application.

Method Area: It stores per-class structures such as the runtime constant pool, field and method data, and the code for methods and constructors. It is shared among all Java Virtual Machine threads.

JMM mapping to underlying machine resources

Each component of the JVM memory model maps to the underlying hardware resources in the following way:

Heap: The heap is stored in the main memory (RAM) of the computer. It's where all class instances and arrays are allocated. The size of the heap can be adjusted with JVM options, but it's limited by the total amount of RAM available on the machine.

Stack: Each thread's stack is also stored in the main memory. It contains frames that hold local variables and partial results, and also plays a part in method invocation and return. Each frame is created at the time of method invocation and destroyed when the method invocation completes, whether that completion is normal or abrupt (it throws an uncaught exception).

Program Counter (PC) Register: The PC Register is a pointer to the memory address of the instruction currently being executed by the CPU. It's a part of the CPU's internal set of registers. In the context of the JVM, each thread has its own PC Register.

Native Method Stack: This is also stored in the main memory and contains all the native methods used in the application.

Method Area: The Method Area is a part of the heap and is also stored in the main memory. It contains per-class structures such as the runtime constant pool, field and method data, and the code for methods and constructors.

Share resources implications

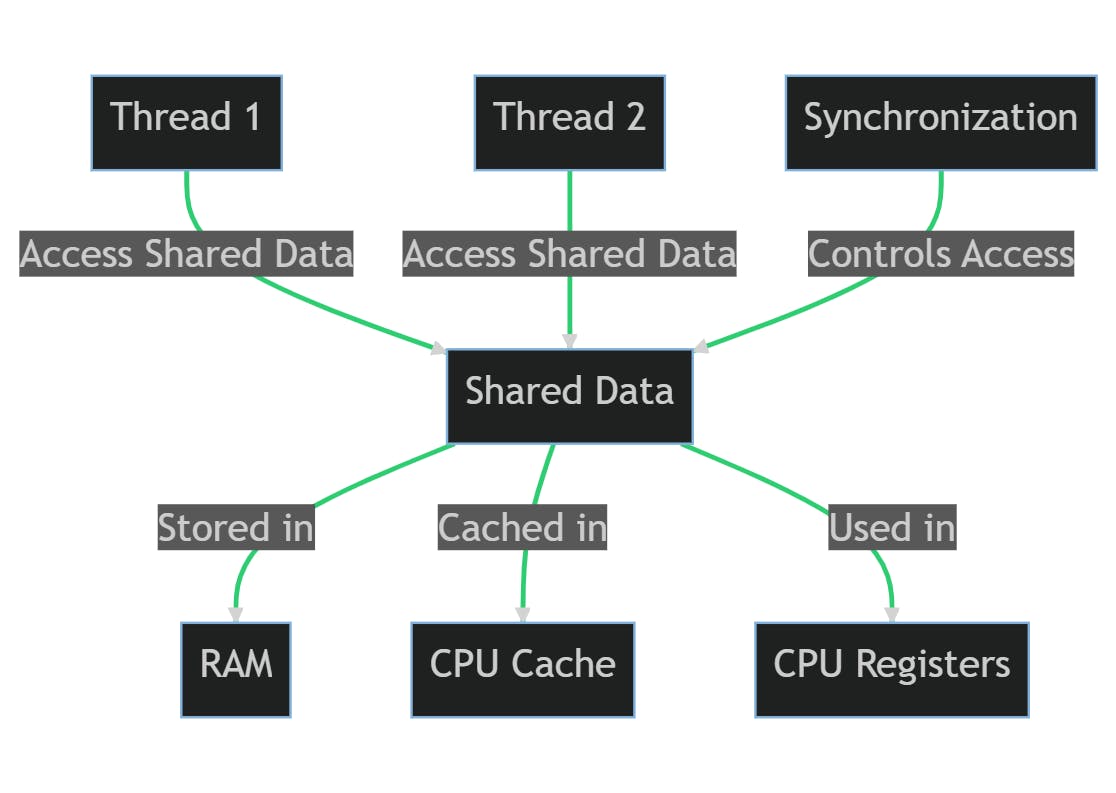

As we already mentioned, shared resources between threads might cause data inconsistency or corruption. The need for synchronized access becomes particularly important when considering the underlying hardware memory, data caching, and registers.

Hardware Memory (RAM): When multiple threads are running concurrently, they may try to access and modify the same memory location simultaneously. Without proper synchronization, this can lead to inconsistent and unpredictable results, a situation often referred to as a race condition.

Data Caching: Modern CPUs have multiple levels of caches (L1, L2, L3) that store frequently accessed data to speed up processing. When multiple threads run on different cores of a CPU, each core may have its own cached copy of the data. Without synchronization, one thread might modify the data in its cache, but this change won't be immediately visible to other threads running on different cores, leading to inconsistent views of the data.

Registers: CPU registers are used to store intermediate data during computation. If two threads are scheduled on the same CPU core and they don't properly synchronize their access to shared data, one thread might overwrite the register values used by the other thread, leading to incorrect results.

Synchronization mechanisms ensure that only one thread at a time can access a shared resource. This prevents race conditions and ensures that all threads have a consistent view of the data, even in the presence of CPU caches and registers.

Let's consider a simple example of two threads trying to increment the same integer value without synchronization.

class Counter {

int count = 0;

public void increment() {

count++;

}

}

class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

Counter counter = new Counter();

Thread thread1 = new Thread(() -> {

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

counter.increment();

}

});

Thread thread2 = new Thread(() -> {

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

counter.increment();

}

});

thread1.start();

thread2.start();

thread1.join();

thread2.join();

System.out.println(counter.count);

}

}

In this example, we have two threads (thread1 and thread2) that are both trying to increment the count variable in the Counter object 10,000 times. If the threads were perfectly synchronized, we would expect the final value of count to be 20,000. However, if you run this program, you'll find that the output is often less than 20,000.

This is because the increment() method is not atomic. The count++ operation actually involves three steps:

Read the current value of

count.Increment the value.

Write the new value back to

count.

Without synchronization, it's possible for both threads to read the value of count at the same time, increment it, and then write it back, effectively causing one of the increments to be lost.

This situation is directly related to how the operating system's thread scheduler works.

The thread scheduler is a part of the operating system that decides which thread should run at any given time, as I mentioned before. This is necessary because there are usually more threads than there are CPU cores, so the scheduler has to multiplex the available cores among the threads.

The scheduler can switch the executing thread at any time, a process known as a context switch. When a context switch occurs, the current state of the thread (including the values of its CPU registers) is saved, and the state of the new thread is loaded. After the switch, the new thread continues from where it left off.

In the context of the previous example, a context switch can occur in the middle of the increment() method. For example, one thread might read the value of count, then get suspended by the scheduler. Then the other thread could run, read the same value of count, increment it, and write it back. When the first thread resumes, it will still have the old value of count in its register, so it will increment the old value and write it back, effectively overwriting the increment done by the second thread.

Synchronization techniques in Java

Before taking a look at different approaches for handling the issue described above, you must understand two important concepts - Atomicity and Critical section:

Atomicity: Atomicity refers to the operations that are performed in a single unit of work without any interruption. When an operation is atomic, it's considered indivisible in the context of other operations. Atomic operations are often used in multithreaded environments to ensure data consistency when multiple threads are reading and writing to shared data. It means that the executing thread cannot be interrupted in the middle of its task, preserving it from working with outdated information. In the above example,

increment()method is a non-atomic operation since it can be sliced into multiple tasks.Critical section: Critical section is any piece of code that has the possibility of being executed concurrently by more than one thread of the application and exposes any shared data or resources used by the application for access.

Having those in mind, thread synchronization is defined as a mechanism which ensures that two or more concurrent threads do not simultaneously execute some particular program segment known as a critical section. In Java, there are several techniques for thread safety and synchronization:

Synchronized Method: In Java, the

synchronizedkeyword can be used to create synchronized methods to control the access of multiple threads to a shared resource. When a thread invokes a synchronized method, it automatically acquires the lock for that object and releases it when the thread completes its task.Synchronized Block: Synchronized blocks in Java are marked with the

synchronizedkeyword. A synchronized block in Java is synchronized on some object. All synchronized blocks synchronized on the same object can only have one thread executing inside them at a time. All other threads attempting to enter the synchronized block are blocked until the thread inside the synchronized block exits the block.Lock Interface: The

java.util.concurrent.lockspackage contains several lock implementations, so you can choose the one that fits your needs best. They offer more extensive locking operations than can be obtained using synchronized methods and statements.Atomic Classes: The

java.util.concurrent.atomicpackage defines classes that support atomic operations on single variables. All operations with these classes are atomic operations and thus can be safely used in a multi-threaded environment.Volatile Keyword: The

volatilekeyword is used to mark a Java variable as "being stored in main memory". More precisely that means, that every read of a volatile variable will be read from the computer's main memory, and not from the CPU cache, and that every write to a volatile variable will be written to main memory, and not just to the CPU cache.Immutable objects: Immutable objects are simple because they can only have one state. Immutable objects are also safe because you can freely share and publish them without the need to make defensive copies. An object is immutable if its state cannot be modified after construction, all its fields are

final, and it is properly constructed, i.e. thethisreference does not escape during construction.

A closer look at how Synchronized works

Here's how the synchronized keyword works at the memory level:

Acquiring the Lock: When a thread enters a synchronized block of code, it needs to acquire the lock on the object the block is synchronized on. If the lock is held by another thread, the entering thread will block until the lock is released.

Memory Flush: Once the lock is acquired, a "memory flush" is performed. This means that all the changes made by this thread to the shared data are flushed to main memory, and the local memory cache of the thread is invalidated so that when variables are referenced in the synchronized block, it will get the latest value from main memory, not from the local memory cache.

Release the Lock: When the thread exits the synchronized block, it releases the lock on the object, allowing other threads waiting on the lock to acquire it. At this point, another memory flush is performed to push any changes to the shared data from the local memory cache to the main memory.

Thread Scheduler: The thread scheduler is indeed involved in this process. The thread scheduler is a part of the JVM that decides which thread should run at any given time. When a thread attempts to enter a synchronized block and finds the object's lock is already held, the thread scheduler can decide to suspend the thread, allowing another thread to run instead. When the lock is released, the thread scheduler can then decide to resume one of the suspended threads.

Thus, the process looks like this:

A thread enters a synchronized block and acquires the lock on the object.

A memory flush is performed, pushing any changes to the shared data from the local memory cache to the main memory.

The thread executes the synchronized block.

Upon exiting the synchronized block, the thread releases the lock on the object.

Another memory flush is performed to ensure all changes are visible to other threads.

The thread scheduler, a part of the JVM, decides which thread should run at any given time. It can suspend threads waiting for a lock and resume them when the lock is released.

Conclusion

It's important to understand that although the Java Virtual Machine implementations are software abstractions, they operate with shared hardware resources available on the underlying machine. Concurrency is a complex topic because it deals with multiple threads of execution upon shared hardware resources over software abstractions. Thus, one should be aware of what is happening under the hood, how concurrency works and what tooling is Java providing to handle potential issues.

![Java Multithreading explained: The Java Virtual Machine abstraction [Part 2]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1684762821062/96ce0f6b-59cb-4980-8132-742b3f0234f6.jpeg?w=1600&h=840&fit=crop&crop=entropy&auto=compress,format&format=webp)